The benefits of therapy dogs for various types of populations, including hospital patients, students, children learning to read, nursing home residents, and others, have been well documented, but how this work affects the dogs themselves has been less studied.

Having made therapy dog visits with Chloe for over six years, I have known a number of teams that have stopped because the handler concluded a therapy dog was burning out.

One handler told me that she took her boxer out of service because the dog had an expression that she had not seen before when a child picked up a fold from the dog’s back.

“He was not happy.

I could not risk that it might go further.”

Concern for stress in therapy dogs was expressed by James Serpell, Raymond Coppinger, and Aubrey Fine in 1999, and various research teams have been looking to identify and measure stress in dogs doing therapy work, with some studies being largely anecdotal, some behavioral, and some looking for chemical markers that might indicate whether therapy dog work is stressful, and when it is too stressful for the dogs. Although levels of oxytocin and insulin have been studied in the search for chemical profiles of stress, the studies discussed here were particularly focused on measuring levels of cortisol. These studies often included measurement of specific behaviors and generally—though not consistently—found that therapy dogs did not have higher cortisol levels while they were doing therapy dog work or had recently completed therapy assignments.

Cortisol is a steroid hormone secreted naturally in response to numerous mental and physical stimuli, some but not all of which are negative and stressful. Cortisol rises in response to sexual stimuli and activities such as hunting and guarding. Also, since dogs have long been valued for waking a village at night at the approach of intruders, it is possible that being approached and petted by strangers, as happens in therapy work, may produce some discomfort and raise cortisol. Short-term effects of elevated cortisol are useful in allowing an animal to regulate bodily responses to situations requiring energy and focus, but prolonged high levels can lead to stress-related diseases and have negative effects on an animal’s health. (Glenk et al., 2014) Therefore, research has begun to focus on a combination of behavioral indications and high cortisol levels to establish that a dog is under stress.

Research Issues

A number of questions have been posed by the research teams involved in this work, which are listed here with pithy summaries of the answers reported so far. After this summary of issues, I will attempt some additional elaboration on some important studies.

- Are cortisol levels higher while therapy dogs are working than when they are at home or in other environments? Some studies say yes, but an increasing number have found no significant difference during or after therapy work. It is not clear that a reconciliation of inconsistent results is yet possible or wise, but I will hazard some thoughts on why the disparate results may have been reached.

- Do the length and frequency of therapy dog work sessions affect cortisol levels? Most studies looked at dogs doing nearly identical regimens of therapy work, though there may be indications that particularly long and frequent assignments lead to elevated cortisol levels.

- Does providing breaks to therapy dogs during work sessions avoid cortisol levels elevating during work days? A study that was designed to answer this specific question found that the breaks made no significant difference in cortisol levels between a group of dogs that got breaks and a control group that did not.

- Does working on leash increase cortisol levels for therapy dogs as opposed to working off leash?A recent study found that working on leash resulted in higher cortisol levels. I will discuss policy implications.

- Are dogs stressed when working with specific target populations? There is some evidence that working with children under age 12 is stressful for dogs, but other groups, such as nursing home residents, Alzheimer’s patients, and drug addicts do not seem to increase canine cortisol levels.

- Does positive reinforcement as a training approach reduce stress in subsequent therapy work by dogs? A number of studies emphasize the use of positive reinforcement in training dogs for therapy work, but this has not been isolated as a factor in identifying which dogs will be more stressed by the work. Because of ethical considerations, I doubt that it will be.

- Are particular canine behavioral patterns correlated with higher cortisol levels? Since some studies did not find higher cortisol levels from therapy work by dogs, correlations could not be provided between behavioral patterns and higher cortisol levels. Nevertheless, a number of research teams have proposed lists of behaviors that should be recorded when seeking to verify that higher cortisol levels indicate stress rather than arousal from some other stimulus. A standard list of such behaviors should be developed so that studies from various research groups can be correlated.

Before looking at individual studies, it is appropriate to provide a summary of their approaches and most important results, which is attempted in the following table. The lead authors and dates of publication are listed in the first row, followed by summary characteristics of the teams, their training, the facilities where they work and what therapeutic functions they have. Because one paper in particular raises the question of whether use of a leash may be a significant stress factor, a row is provided for what information is available from each study in this respect. Finally, a summary of the behavioral and cortisol results is provided.

Figure 1. Characteristics of Dogs, Training, Facilities, Activities, and Results of Cortisol Studies

Paper | Haubenhofer & Kirchengast, 2006 | Piva et al., 2008 | King et al., 2011 | Glenk et al., 2013 | Ng et al, 2014 | Glenk et al., 2014 |

Number of dogs/teams | 18 | 1 | 27 selected (data from 21) | 21 | 15, but one team eliminated because of atypical results | 5 dogs 3-10 years old |

M/F | 15 (4 spayed)/3 (1 neutered) | 1 female intact (sometimes in heat) | 14/13 | 7/14 (all spayed) | 8/6, all fixed or spayed | 3 (2 fixed)/2 (1 spayed) |

Certification/training | Teams members of Tiere als Therapie | Basic obedience commands | Certified by Therapy Dogs, Inc. (Cheyenne) | Austrian AAI organization, certified dogs had ≥ 1 year experience in mental healthcare facilities | Vet Pets, Therapy Dogs International, AAA sessions, averaging visits from an 1 to 10/ month | Certified in Italy for AAI work, all with ≥ 2 years working experience; all trained with positive reinforce-ment and averaging ≥ 1 visit/ month |

Facility/ population | Various facilities (hospitals, rehabilitation centers, retirement homes, schools) | Alzheimer’s patients | Edward Hospital, Naperville, Ill., most patients 41-60 years old, but some children | 8-10 patients | Students in common area of U. Penn. Dormitory, 30 to 56 individuals in same room during study breaks | Drug-addicted inpatients |

Activities | Dogs participate in “all types of work in AAA and AAT,” ranging from 1 to 8 hours (!) | 20-minute AAA sessions | 2-hour shifts, involving petting, hugging, watching the dog (AAT) | 50-60 minute AAI sessions (~AAT) | Highly structured petting, scratching interactions in 60 minute sessions | Multi-professional animal assisted intervention (similar to AAT); sessions 55-60 minutes |

Frequency | Variable number of sessions, sampling over 3 months | 3-4 times/week | 2 sessions/ week | 1 time weekly for 8 weeks | Two 2-week periods during March & April 2012 | 1/week with 8-10 participants (and 1 dog and 2 therapists) |

Use of leash | Not described | Allowed to roam free | Certifying organization requires use of leash, so presumably applied here | For experiments, 7 certified dogs were on leash and 7 were off; dogs in training were on leash | Off leash at home, on leash in novel and AAA environments, but could be attached to collar, harness, or head collar | Off leash |

Reward | Not described | Praise, allowed to be free in garden and chase lizards | 2-minute quiet-play time-out session (found not to significantly alter cortisol levels) | Praise, food treats | Treats prohibited during AAA sessions | Food treats (cheese) were sometimes given, but sometimes only allowed to be smelled to stimulate salivation |

Behavioral stress indications | Not described, though authors recommend several days of rest after each session | Frequency of emotional and behavioral responses and calming signals and body language noted by staff | Stress behaviors such as air licking, yawning, panting, pupillary dilation, and whining were observed more frequently in dogs identified as having higher cortisol levels | No behavioral observations in published article | Ethogram (see next table); only behavioral difference noted was dogs standing more in AAA setting than novel or home; but more in novel than home | No differences in activities on the ethogram were found during working sessions; lip licking and other behaviors also did not indicate stress |

Cortisol results | Salivary cortisol levels significantly higher on days dogs worked; higher in short sessions; generally higher at end of session; higher in morning than afternoon; cortisol levels increased with number of sessions/week | Fecal and hair cortisol measured supported “positive adaptation to the new environment and role of the dog” | 10 dogs showed significant signs of stress, but 11 were either neutral or negative to stress levels of cortisol; experienced dogs were less likely to show stress levels of cortisol | No significant increases in salivary cortisol levels in any of the groups compared to baseline and home levels; positive interactions, quiet play, and affiliate behaviors were linked to reduced cortisol levels; dogs on lead showed high cortisol levels than dogs off lead | Cortisol measure in home, administrative office (novel), and dorm (AAA) environments; no significant difference between home and AAA environments | Salivary cortisol levels indicate dogs were not acutely stressed, but significant decreases were only found in experienced therapy dogs working off leash. |

Undoubtedly more studies will be released in the coming months and years, but the following will provide a picture of some of the more dramatic results reported so far.

2006 Study Finding Elevated Cortisol Levels in Dogs after Therapy Work

Two researchers from the Institute of Anthropology at the University of Vienna, Dorit Karla Haubenhofer and Sylvia Kirchengast (2006), studied salivary cortisol levels in 18 therapy dogs, 15 females (4 spayed) and 3 males (1 neutered). All dogs were members of an Austrian therapy animal organization, Tiere als Therapie. The working methods of the dogs were apparently variable as a “therapeutic session was defined as one visit to a facility and included all types of work in AAA and AAT.” Sessions ranged from one to eight hours, though longer sessions apparently involved many breaks.

The number of sessions in which teams participated in the three-month period during which measurements were taken ranged from 9 to 50, so a team that had 50 sessions could have been averaging visits almost every other day. The authors found that cortisol concentrations were significantly higher on days that the dogs did therapy work than on other days. Cortisol levels after sessions were generally significantly higher than those taken before sessions began. Also, this was more pronounced in the morning than the afternoon, and was higher in short sessions than in long ones. The number of sessions per week was an important factor:

“Another variable related to physiological arousal was the number of therapeutic sessions done each week, with cortisol concentrations increasing significantly with the number of sessions. This suggests that several days of rest after each therapeutic session might prevent extreme arousal, which could lead to signs of chronic stress.”

Although cortisol levels were higher in short sessions than long sessions, it seems that the intensity of the work for some of the participants was very high, and eight hours in a therapeutic environment is not something I have personally encountered at any institution or facility. The general nature of the description of the sessions, “all types of work in AAA and AAT,” makes speculation as to how these results may be correlated with others difficult.

The Time-Out Study

Two researchers from the Biology Department of Northeastern Illinois University and one from the Chicago Zoological Society, King et al. (2011), looked at both behavioral factors and cortisol levels in dogs working in animal-assisted therapies (AATs). A specific purpose of the study was to determine whether therapy dogs allowed to have a quiet-play, time-out session during a working shift would “show fewer signs of stress both physiologically and behaviorally.” A quiet-play, time-out session was described as consisting “of 2 minutes of visiting with the handler, allowing the dog to chew on a toy, petting and talking to the dog, or providing mental stimulation in the form of obedience commands.”

A total of 27 therapy dog teams were recruited, with 14 female and 13 male dogs, but 6 dogs were dropped from statistical sampling for various reasons. Handlers had scheduled two-hour shifts at the Edward Hospital in Naperville, Illinois. They note that this environment often involved “gathered crowds of people, or alarms on hospital equipment.” Dogs were certified through TDI, which apparently here means Therapy Dogs, Inc. of Cheyenne, Wyoming (i.e., not Therapy Dogs International).

Participating handlers filled out a survey providing information concerning the dog’s behavior during sessions and “the age of the patient the therapy dog visited, and the type of interaction between the patient and the AAT dog.” Most patients visited by the dogs were between 41 and 60 years old. Most engaged the dogs by petting, but some by hugging or just watching the dog. A researcher also observed the dog’s behavior at the AAT office in the hospital after each work shift, recording, in particular, “panting, air-licking, tremor, pupillary dilation, or yawning 3 times.”

As to the question of how a quiet-time session would affect cortisol levels, the researchers found no significant difference between dogs that had such sessions and those that did not. Some handlers did report “an initial hesitation in the dog when they returned to work after the time-out session.” They also found that “AAT-hander survey reports were consistent with physiological indicators of stress,” though “cortisol levels decreased in several dogs at the end of their work shift, whether they had the ‘quiet-play’ time-out session or not.”

This and the previous study are frequently cited as examples of results indicating that therapy work can be stressful in dogs. Although I have encountered handlers who take their dogs for shifts as long as two hours, I have always restricted visits with Chloe to about one hour. This was not initially my own limitation but because I sensed that Chloe’s interest in visiting more people in hospitals and nursing homes declined after about an hour. Again, I wonder if the length of the sessions was a factor in producing stress.

Shelter Dog in Alzheimer’s Facility

An early study that did not find unusual cortisol levels in a dog at an Alzheimer’s facility was somewhat different from other studies discussed here because the dog was not brought to the facility by a handler, but was “rehomed” to live in the facility after being at a shelter. (There has been some legal recognition of such resident companion animals in the United States. See Service and Therapy Dogs in American Society, at 104.) The research team, composed of veterinarians from the University of Bologna, Piva et al. (2008), chose Daisy, a six-year-old intact female English setter, from a group of eight candidates for the project. Daisy was chosen because she was kind and cooperative when handled by strangers, interested in people, lacked aggression, was not excitable, had a stable and tolerant temperament, and acquired and carried out simple obedience commands easily. The commands included Sit, Come, Wait, Sit on the Chair, and Down.

![]() |

| Daisy (courtesy Dr. Elisabetta Piva) |

Daisy was gradually introduced to the facility,

initially by weekly visits, first with employees, then with patients. Meetings were held in a large room where she had the opportunity to escape.

Finally, she was allowed to explore the entire facility and randomly meet patients and employees.

Once in residence, Daily began to have 20-minute AAA sessions three to four times a week with four Alzheimer’s patients chosen by the staff psychologist.

“These sessions include activities such as calling the dog from varied distances with vocal commands or gestures, brushing, playing, walking, feeding, and using hand signals to practice obedience exercises, depending on the patient involved.” After sessions, Daisy was allowed to unwind and praised for relaxing. She was also offered the chance to be free in the garden where she could hunt lizards.

Cortisol levels were measured:

“Fecal cortisol levels were evaluated in samples collected from every spontaneous defecation during the gradual introduction phase starting 2 days before to 2 days after each visit, and 2 days before to 7 days after adoption. An increase in fecal cortisol concentration indicates an activation of the adrenocortex in response to stressful conditions….”

The researches argued that their “findings suggest that despite small changes in the environment (more human patients in the facility) and in daily routines (fewer walks outside during AAA because of the hot and sometimes stormy summer weather that was considered dangerous for elderly people), the dog was healthy and her level of social interaction, exploration, and playfulness increased during the course of the AAA program. The dog displayed no aggressive or sexual behavior, even when in heat. Autogrooming detected previously decreased in frequency and an acral lick granuloma that she had had gradually disappeared. Over-grooming, shown frequently by Daisy during the first examination in the shelter, was displayed less frequently as time went by in her new social and physical environment.”

The authors concluded:

“Daisy was able to cope with the new environment. The presence of enriched social contacts and the opportunity of increased physical activity positively affected her well-being…. The hormonal trend, especially with hair cortisol, seems to be correlated with the clinical and behavioral findings, all supporting a positive adaptation to the new environment and role of the dog…. Although this report refers to a single subject, Daisy, the results of our work represent an encouraging basis for further studies on a wider scale. Our dog, besides her ability to adequately carry out AAA sessions, showed progressive benefits (re-homing, increased activity and social interaction, decreased signals of stress), as definitively assessed by statistical analysis.”

Although not highlighted in the results, Daisy was frequently off leash, which may be significant in light of a study to be discussed below. The results also suggest that Alzheimer’s patients are not inherently stressful subjects for a therapy dog to work with.

Leash Study

Six researchers from a number of institutions in Austria, Glenk et al. (2013), sought to measure changes in salivary cortisol levels of dogs participating in animal-assisted interventions (AAIs, essentially AAT sessions), collecting samples on working and non-working days of 21 dogs. The researchers concluded that both therapy dogs and therapy dogs in training were not stressed by their participation in the activities. They did detect, however, that cortisol levels were significantly different depending on whether the dogs were working on- or off-lead in the sessions. The paper argues that the effect of a leash on cortisol levels of therapy dogs may have been underestimated. Beerda et al. (1998) had previously demonstrated that pulling dogs on a lead cased increases in cortisol when the dogs were confronted with sudden noises or electroshocks.

Teams were recruited from an Austrian AAI organization whose members regularly work in dog-assisted group therapy. All handlers were women who also took part in the therapy sessions. An experimenter also attended the sessions for sampling procedures, with the approval of staff members of the facility where the sessions occurred. Seven dogs were males and 14 were females, ranging from 1.5 to 14 years. Nine of the females were spayed, but the other females were not in estrus or pregnant during the experiments.

To become a certified therapy dog team, “dogs and owners undergo special training, during which animal handlers can decide whether they want to work with their dog on- or off-lead.” This is not typical in the United States. The rules of the organization to which Chloe and I belong provide: “Dogs must be kept on leash at all times when visiting, except when warranted (during a demonstration).” There was another significant difference from my experience. Among interaction behaviors recorded during the study were food treats being given to the dogs. My organization's rules state that the “use of food or treats is prohibited while visiting (exception—during a demonstration, the handler can treat the dog).”

There were three groups used for the study, one group of dogs trained to work on lead (CTD-ON, in the acronym used in the paper), and another group off lead (CTD-OFF). Dogs used for the study “had a minimum of one year working experience in mental healthcare facilities.” The third group consisted of dogs that were in training (TDT-ON), whose owners had not yet decided whether to work on- or off-lead, but which were on lead for the experiments. There were seven dogs in each group. The existence of such a training stage indicates a higher level of training than is often found for therapy-dog qualification in many countries.

Sessions lasted 50 to 60 minutes and were described as follows:

“All therapy sessions consisted of theory parts, interpersonal communication and interaction parts with the therapy dog. Each therapy programme started with a group of ten adult patients and was run weekly for eight weeks with the same individuals (animal handler, therapy dog and patients) present. There was no patient turnover during these eight weeks. AAI programmes were supervised by each institution’s staff members and participation depended on the respective physical or psychological condition of the patients. In the experimental sessions, 8–10 patients were present. The patients were informed previously how to interact in an appropriate way with the therapy dog before the dog was first introduced to the group. During therapy, the patients were seated in chairs and instructed by the animal handlers when and how to interact with the dog (ie stand up, call, touch, grab or pull the dog’s lead).”

Certified dogs participated in the sessions while dogs in training watched and did not interact with the working dog. Dogs were trained and handled by “positive reinforcement and gentle handling.” Salivary cortisol was measured at home, before and after AAI sessions, and on non-working days. Saliva samples were also collected during some therapy group sessions.

“[O]ur study results reveal that performance in group-AAIs in adult mental healthcare did not stimulate significant increases in salivary cortisol stress responses in CTD-ON, CTD-OFF or TDT-ON when working cortisol levels were compared to baseline levels and home levels. These are important findings, considering that in dogs, an elevation in cortisol has been associated with stressful conditions resulting from fear…. On the other hand, positive interaction with humans, quiet play and affiliate behaviours were linked to reduced cortisol levels in dogs….”

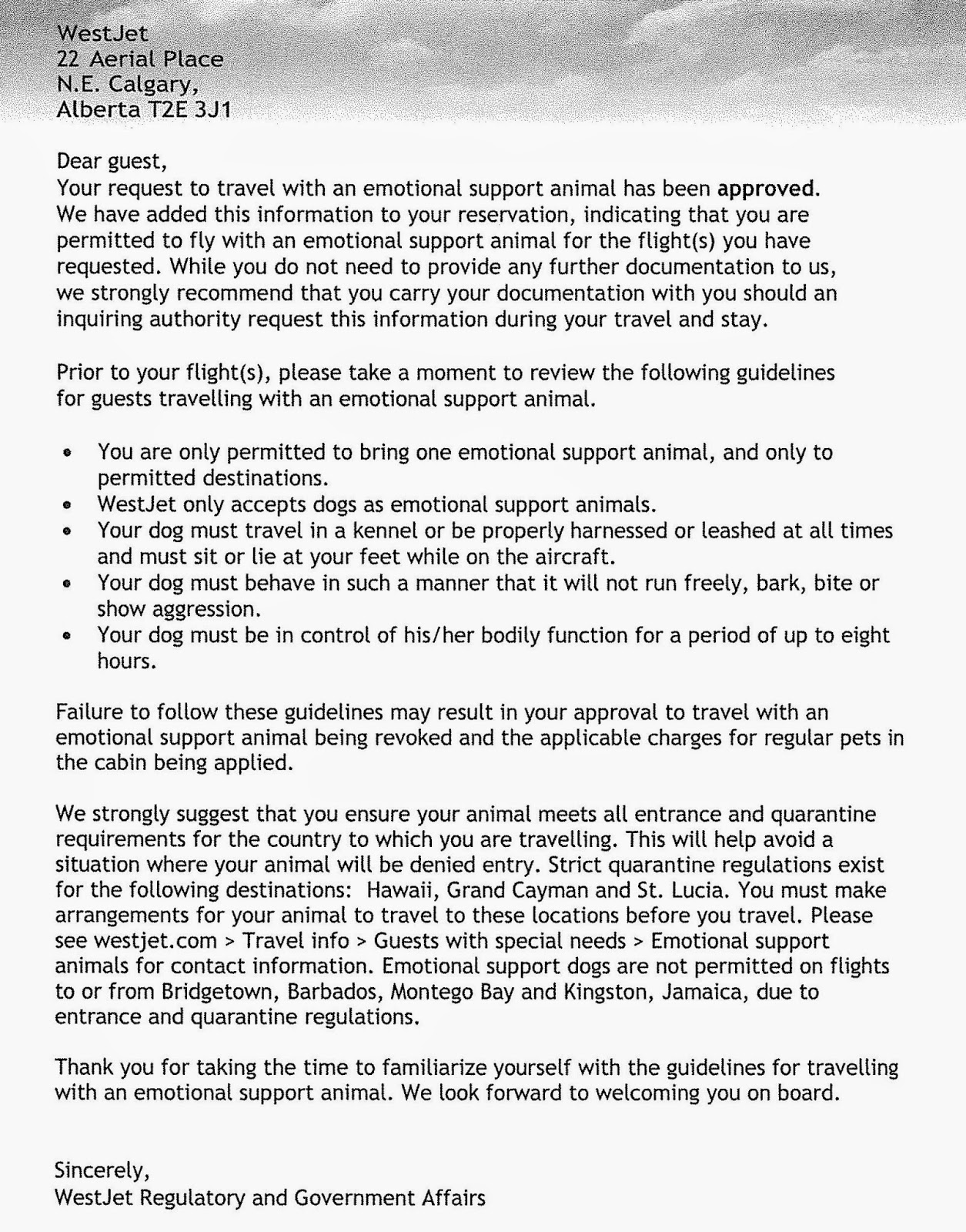

![]() |

| Cortisol Levels Before and During Sessions (courtesy Dr. Lisa Glenk) |

The graphic from the paper shows that before therapy (Time 1a) dogs in the three categories, two with leashes (but one in training) had fairly similar cortisol levels, but during therapy (Time 1b), they separated substantially, with dogs off leash having lower cortisol levels then dogs on leash. Dogs in training, with leashes, had the highest levels. As noted above, Beerda et al. (1998) had determined that being pulled on a lead caused stress in dogs and increased cortisol levels, so these results were not surprising.

The longer sessions lasted, the more cortisol levels may have declined in CTD-ON dogs, but more research will be needed to verify this. The team notes that there may be some differences between handlers that prefer to work with dogs on lead and those that do not, meaning perhaps that more controlling handlers might add some stress to the therapy situation. On the other hand, “animal handlers with therapy dogs on the lead should be aware of subtle signals of discomfort in their dogs when they interact with patients and react accordingly.” My own experience over six years of therapy dog work confirms this. I have no choice but to work on leash, but more than a few times I have felt that a patient or other individual in a therapy dog visit was discomforting Chloe in some way, perhaps slapping rather than petting, or smothering her, and I have had to extract her from the setting as tactfully as possible.

As to why Hubenhofer and Kirchengast (2006) and King et al. (2011), both discussed above, reached different conclusions, this paper speculates:

“[I]t is likely that the AAIs investigated by the different authors are not directly comparable because of their different conceptual context (eg therapy content, single patient versus group interventions, familiar versus unfamiliar patients), environment (eg therapy facility such as hospital, prison, geriatrics) and arrangement (eg frequency, intensity and duration of human-animal contact, dog on/off the lead, refuge for the dog).”

This is an important observation. With the limited number of cortisol and cortisol/behavior studies of therapy dogs conducted so far, more patterns regarding the effects of different types of institutions and different types of programs may come to light.

Substance Abuse Facility

The same Austrian team published another paper in 2014, looking at behavior and cortisol levels in therapy dogs that participated in sessions at an in-patient substance abuse treatment facility, measuring cortisol levels before and after sessions. Levels of the chemical decreased in all sessions. “There was no difference between salivary cortisol levels sampled on a nonworking day at home and work-related levels sampled at the therapy site. None of the behavioral parameters varied significantly over the course of the 5 MTI [multiprofessional animal-assisted intervention] sessions.” MTI, according to the authors, “meets all require criteria to be considered AAT … and is carried out by 2 human experts with a back ground in psychology, pedagogy, life science, and/or social science….” The paper elaborates:

“Mediated by the MTI professionals, patients used signals to communicate with the dog. These signals were verbal or nonverbal cues including different hand signs, eye contact, mimics, words, and tone of voice. The main goal of MTI is to enhance patients’ emotional and social competence through implicit learning during interaction with a therapy dog…. Accordingly, the participants had been instructed how to interact in an appropriate way with the therapy dog before the dog was introduced to the group. Human-animal contact was initiated by the freely moving dog, which was kept off lead. Human-animal interaction behaviors moreover included verbal contact, where people talked to the dog or spoke in a high-pitched/fluctuating voice to praise the dog. Tactile contact included softly touching, stroking, and/or grooming the dog. To play with the dog, people used dog toys and/or gently gestured with hand, arms, and fingers. For ethical reasons, dogs were never forced into positions and were able to lie down, drink water, or leave the therapy room at any time.”

The researchers concluded that therapy dogs “are not being stressed by repeated participation in in-patient substance abuse therapy sessions.” They argue that therapy dog handlers need more guidance:

“The development of a practitioner’s guide on dog welfare for AAI professionals and, maybe even more importantly, AAI volunteers shall be a forthcoming endeavor. AAI volunteers are often very dedicated to their work, but they also need to be well aware of subtle signs of discomfort in their dogs. Future research still needs to identify the populations or situations where contact with therapy animals may be potentially problematic or inappropriate for either the animals or the people involved….”

This also is an important observation. As additional research establishes what sorts of conditions might produce stress in dogs, handlers should receive additional instruction in how to recognize stress. At the moment, most qualification examinations in the U.S. that I have encountered through my own experience or that of others primarily involves testing the dog’s ability to follow the handler’s commands, not whether the handler can read signals given by the dog.

Ethogram Study

Four researchers at the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine and two from the vet school at the University of Pennsylvania, Ng et al. (2014), sought to quantify the stress effects on therapy dogs from engaging in animal-assisted activities (AAAs). This team sought to determine how stress levels would differ for therapy dogs in three environments: their homes, a novel setting, which was an administrative area in Penn’s vet school, and AAA sessions with college students in the communal area of a residence hall.

Dogs were either part of the University of Pennsylvania’s therapy dog program (Vet Pets) or dogs registered with Therapy Dogs International. All participating dogs were fixed or spayed, seven females and eight males. Five had been certified for only one year, but one had been certified for six years and one for eight.Some averaged only one therapy dog visit per month, but one averaged between seven and ten days per month. Session lengths from the experience of the handlers could be as low as half an hour and as high as two hours. Of 15 dogs, only two had male handlers.

Saliva was collected after the handler and dog had been in each of the three settings for an hour. The researchers state that the “goal of the novel setting was to allow the dog to act as it typically would with its owner when waiting in an unfamiliar environment for 60 min without stranger interaction.” Sometimes two of the teams were in the administrative location simultaneously, though dogs were limited to interacting only with their own handlers in the location.

The AAA sessions were with undergraduates in a communal space of Rodin College House, a Penn dorm. The room was often used by students for study breaks and there were between 30 and 56 individuals present in the room during the sessions. The researchers elaborate:

“The room was 9.1 m × 9.1 m, with tables and chairs arranged to evenly spread and demarcate eight, 2.1 m × 2.1 m spaces for each dog-handler team to remain during the session. The dog remained in close proximity to the handler on a1.83-m leash attached to a collar, harness, or head collar that the dog was accustomed to wearing at AAA visits. A maximum of eight dogs used separate spaces of the room simultaneously, but dogs were restricted from interacting with one another.”

The AAA sessions were highly structured with interactions and saliva collection kept in specific sequences:

“Participants were instructed to approach the dog from the side, to extend a hand to allow the dog to sniff, and to pet gently. Participants were instructed to avoid the following: aggressive gestures, making loud noises, leaning over the dog, giving treats, and crowding around the dog. Assigned “petters” were assigned to pet specific dogs during the 5-min petting time … but participants were permitted to interact with any of the dogs outside of that time….

“Each petter was instructed to sit on the floor to the side of the dog opposite the handler, where the petter did not obstruct the video camera view of the dog. In all settings, each petter was instructed to sit next to, rather than facing, the dog and gently stroke, pat, massage, and/or scratch the dog anywhere on the body with at least one hand remaining on the dog at all times. The dog was to be allowed to position itself and behave as it wanted during the 5-min petting procedure, as long as it remained within the assigned space within view of the video camera (accomplished via leash).”

Saliva was collected every half hour as prior research by Vincent and Mitchell (1992), and Handlin et al. (2011) had found significant changes in cortisol levels 15 to 30 minutes after stress events.

The study also involved looking at behavioral changes in the three distinct environments. Sessions were videotaped and behavioral patterns of the dogs, particularly while being petted, were analyzed. An ethogram, a list of behaviors divided into postural states, spontaneous events, oral behavior, and alertness was completed by analysts of the tapes. (See Figure 2, below.) Postural states included sitting, standing, recumbent, ambulating, exploring, and crouching. Exploring is defined as “moving slowly, sniffing, investigating the environment.” Crouching is defined as “rapid, pronounced lowering of posture, sometimes in combination with movements that enlarge distance to eliciting stimulus; posture shows lowered position of tail, backward positioning of ears, legs bent.”

Spontaneous events were subdivided into eight categories: paw lifting, vocalizing (any form), scratching, body shaking, trembling, jumping (“springing into air, either to make contact with an object or person or for no apparent reason”), repetitively moving head (continuously for more than three seconds), and stretching. Oral behavior could be panting, neutral (mouth closed), mouth opening (“opening, closing mouth with rapid movements without extending tongue; possibly yawning”), lip licking (“includes tongue out: tip of tongue briefly extended; snout licking: part of tongue shown, moved along upper lip; swallowing; smacking”), licking person, licking object, and self-grooming (“oral behaviors directed toward dog’s own body (licking, chewing skin and coat)”). Alertness was divide into two categories: alert (“eyes kept open”), and rest/sleep (“eyes closed, dog inactive > 10s”).

The reason for looking at both cortisol levels and behavior is explained as follows in the paper:

“It is important to consider that the same behavior can correspond to different emotional states of the dog. For example, ambulating may be strictly a motor behavior, but it can also be an indicator of restlessness or anxiety, depending on how the behavior is performed and the type of concomitant behaviors present at the time of ambulating. Therefore, it is necessary to assess behavior in conjunction with a physiologic parameter such as cortisol.”

The only behavioral differences noted had to do with postural states. As to behavior, dogs stood significantly more of the time in the residence hall than the other settings, but more in the administrative area than at home. They also spent more time ambulating in the residence hall, but very little in the administrative area and almost none at home. Recumbent time was highest at home, which is no surprise, but at 60 minutes was higher in the residence hall than in the administrative offices, while at 90 minutes was higher in the administrative offices than in the residence hall. The researchers speculated that in the administrative offices, the environment was unfamiliar and the dogs “were hyper vigilant to disturbances outside the room.”

The researchers conclude:

“The 60-min AAA for college students in a dormitory setting did not appear to cause significant HPA activation or increases in stress-associated behaviors in registered AAA dogs…. No physiologic or behavioral indicators of stress, fatigue, or exhaustion were present during the AAA, suggesting that this particular AAA with college students did not negatively impact the welfare of these dogs. Furthermore, salivary cortisol was higher in the novel setting, which may be explained by the unpredictable nature of the setting.”

They speculate that “dogs were likely not stressed during the AAA because it was a familiar and predictable situation.” In the novel setting, the administrative offices, the dogs may have been slightly stressed by an inability to predict what would happen next. Although the dogs were not in direct contact with the veterinary hospital, the researchers note that they “could have detected subtle cues of a veterinary hospital environment. Therefore, the physical environment alone, especially a veterinary hospital setting, may be physiologically stimulating, irrespective of the activity performed.”

As discussed, this study did not look at dogs in AAT settings, just AAA settings. The researchers note that “there is no single validated model to test the effect of AAA or AAT because they vary greatly in intensity of interaction, duration, objectives, and demographics of recipients.” Thus, an AAT session, which “typically involves a continuous interaction with a single or small group of individuals,” might be more stressful for dogs.

The researchers argue that their study describes “a rigorous method of assessing welfare in AAA dogs that can be applied in larger populations of working dogs.” This proposition should be considered by other research teams entering this area. Consistency of research designs will help determine whether and when dogs are being stressed by therapy work.

Summary

Variations in the studies as to the numbers of teams, the training and certification approaches, the types of facilities visited, what activities were conducted inside those facilities, and the length and frequency of visits and sessions, means that comparing studies so far published cannot assure solid conclusions. American and European studies differ in that the former generally involved dogs working on leashes, without food treats, whereas European studies sometimes involved dogs moving freely in therapeutic settings and receiving food treats from handlers and sometimes others. Attempts to specify behavioral indicators of stress have had limited success, and correlations with cortisol levels have proved elusive.

Arguments, such as that made by Ng et al., that a uniform grading system for behavioral measurements would be desirable, should be adopted, perhaps after some major conference on stress and trained dogs. The behavioral measures suggested by four of the major studies discussed here are listed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Behavioral Measures in Cortisol Studies

Piva et al. (2008) | King et al. (2011) | Ng et al. (2014) | Glenk et al. (2014) |

Nose and lip licking Sit or curl up Lie down, also with head Yawning Closing eyes Rapid eye movement Hypervigilance Walking, pacing Circling Low posture Freezing Stereotypes Displacement activity Redirect activity Apathy | Panting Pupillary dilation Yawning Whining Air licking | Postural state: Sitting Standing Recumbent Ambulating Exploring Crouching

Spontaneous event: Paw lifting Vocalizing Scratching Body shaking Trembling Jumping Repetitively moving head Stretching

Oral behavior: Panting Neutral (mouth closed) Mouth opening Lip licking Licking person Licking object Self-grooming

Alertness: Alert Rest/asleep | Activity: Lay Sit Stand Walk Run

Behavior: Lip licking Yawning Panting Paw lifting Body shake Tail wagging

Response to human action: Takes a treat Obeys command |

Arguably, a set of behaviors and a recording system should be used for stress studies of dogs doing not only therapy work but also service, police, rescue work, etc.

Conclusion

The standard U.S. requirement that dogs be on lead during therapy visits does not come solely from certifying organizations or the mandates of their insurance providers. Recently, a hospital I have visited with Chloe went through a national accreditation process where one dog, which was regularly turned loose in the psychiatric ward, was banned from the hospital because the accrediting organization stated that therapy dogs visiting the hospital had to be on a leash at all times. This is also required by some insurance policies for hospitals. Nevertheless, therapy dog organizations should give further consideration to whether working with therapy dogs off leash might be appropriate in certain confined spaces and structured activities, and if necessary, engage other stakeholders in therapy dog work in discussions on this issue. It might be appropriate for certifying organizations to consider advanced certifications for dogs that are capable of working off leash under voice command of the handler. Progress in this area might require the major therapy dog organizations to cooperate with each other.

As discussed, most target populations caused and most research designs found no evident stress in dogs from therapy work. Nevertheless, Marinelli et al. (2009b) found that the age of individuals involved in animal-related activities and therapies “influenced the expression of stress-related behaviors” in dogs in that more such behaviors were evident when dogs were with children under 12 years of age. This has been my experience as well. When Chloe turned six I stopped going to a facility for developmentally disabled children because one teacher who had often accompanied me on visits to the classrooms left and too many other teachers regarded my entry into the room as time to attend to other matters. The children often overwhelmed Chloe. As she has gotten older, I have become more concerned with experiences that I sense, without any chemical or scientific behavioral analysis, may be stressful for her.

These studies do not negate the importance of the handler knowing his or her dog and sensing when it is time to go home or to stop working. Even the most sophisticated behavioral analysis, with video cameras and behavioral patterns categorized down to seconds if not microseconds, cannot replace the instincts of a good handler. Nor can handlers be automatons created complete and unchanging after passing a certifying examination. My work with Chloe has evolved over many years, and I have grown to trust my sense of how she can be most effective, and what will be most helpful to a patient, resident, student, or other person we are visiting when she is working. She looks at me when she wants me to realize that it is time to move on, or that the patient has had enough. She has also grown into the work. Any long-term handler with an experienced therapy dog will say much the same.

Stress research is a promising area and all those involved or interested in therapy dog work, whether as handlers, trainers, certifying organizations, recipient institutions, or policy makers, should be paying attention as more results come in.

Sources:

Beerda, B., Schilder, M.B.H., van Hooff, J.A.R.A.M., de Vries, H.W., and Mol, J.A. (1998). Behavioural, Saliva Cortisol and Heart Rate Responses to Different Types of Stimuli in Dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 58, 365-381.

Ferrara, M., Natoli, E., and Fantini, C. (2004). Dog Welfare During Animal Assisted Activities and Animal Assisted Therapy. Tenth International Conference of the IAHAIO. Glasgow, Scotland (finding dogs did not show stressed behavior from AAT and AAA sessions).

Glenk, L.M., Kothgassner, O.D., Stetina, B.U., Palme, R., Kepplinger, B., and Baran, H. (2013). Therapy Dogs’ Salivary Cortisol Levels May Vary During Animal-Assisted Interventions. Animal Welfare, 22, 369–378.

Glenk, L.M., Kothgassner, O.D., Stetina, B.U., Palme, R., Kepplinger, B., and Baran, H. (2014). Salivary Cortisol and Behavior in Therapy Dogs During Animal-Assisted Interventions: A Pilot Study. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research, 9(3), 98-106.

Handlin, L., Hydbring-Sandberg, E., Nilsson, A., Ejdeb, ck.M., Jansson, A.U., and s-Moberg, K. (2011). Short-Term Interaction between Dogs and their Owners: Effects on Oxytocin, Cortisol, Insulin and Heart Rate: An Exploratory Study. Anthrozoos Multidisciplinary Journal. People and Animals, 24, 301–315.

Marinelli, L., Mongillo, P. Salvadoretti, M., Normando S., and Bono, G. (2009a). Welfare Assessment of Dogs Involved in Animal Assisted Activities. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research, 4, 84-85. (Salivary cortisol levels and behavioral indications of acute stress were not elevated in therapy dogs visiting a retirement home over a period of seven weeks.)

Marinelli, L., Normando, S., Siliprandi, C., Salvadoretti, M., and Mongillo, P. (2009b). Dog Assisted Interventions in a Specialized Centre and Potential Concerns for Animal Welfare. Veterinary Research Communications, 33 (Supplement 1), S93-S95.

Ng., Z.Y., Pierce, B.J., Otto, C.M, Buechner-Maxwell, V.A., Siracusa, C., and Were, S.R. (2014). The Effect of Dog-Human Interaction on Cortisol and Behavior in Registered Animal-Assisted Activity Dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 159, 69-81.

Odendaal, J., and Meintjes, R.A. (2003). Neurophysiological Correlates of Affiliative Behavior Between Humans and Dogs. The Veterinary Journal, 165, 296-301.

Piva, E., Liverani, V., Accorsi, P.A., Sarli, G., and Gandini, G. (2008). Welfare in a Shelter Dog Rehomed with Alzheimer Patients. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 3, 87-94.

Serpell, J.A., Coppinter, R., Fine, A.H., and Peralta, J.M. (1999). Welfare Considerations in Therapy and Assistance Animals: An Ethical Comment. Chapter 18 in Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy” Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice. New York: Academic Press, 415-431. (The chapter has appeared in two subsequent editions of this book.)

Vincent, I.C., and Michell, A.R. (1992). Comparison of Cortisol Concentrations in Saliva and Plasma of Dogs. Research in Veterinary Science, 53, 342–345.

%2BCu%2BFaoil%2B%26%2BAnka%2BFriedrich%2C%2BWikipedia.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)