George Washington loved the chase, and engaged in it with hunting hounds through most of his life. Diary entries and correspondence refer to hunts of deer, fox, hare, and pheasant. Hunting hounds at Mount Vernon came from English and American stock and, after the war, from France, though the French dogs may have been something of a disappointment. Besides foxhounds, Washington mentions water dogs (spaniels), pointers, terriers, mastiffs, and curs. He had heard of Irish wolfhounds and for a time sought to get some to reduce predation of his flocks.

Washington personally treated the ailments of his dogs, for instance applying a concoction of hog’s lard and brimstone when mange spread through a kennel. Washington was particularly interested in rabies, and at least once shot a rabid dog. He corresponded with Dr. James Mease, who conducted research on the nature of the disease. In 1797, he sent a slave, Christopher, to Dr. James Stoy near Philadelphia in hopes that medical attention could avert the consequences of the bite of a mad dog. The slave did not become sick.

The first president’s attitudes towards dogs were those of the aristocrats of Virginia, at least those of English descent, but also reflected concerns about why slaves might want dogs, particularly when sheep or other livestock might be stolen with their help. Although Washington took great care with his own dogs and those of his friends he borrowed for the chase, his concerns about sheep stealing led him to order that a slave should only own one dog, and if any slave owned more, overseers were to kill the excess by hanging the dogs. It is not clear that this was ever enforced, but Washington certainly wanted his overseers, and his slaves, to believe that it would be.

The Wessyngtons of County Durham

Sometime around 1183 AD, Washington’s ancestor William de Hertburn exchanged the village of Hertburn for the manor and village of Wessyngton in a land transaction whereby William agreed to attend the bishop of Durham with two greyhounds in grand hunts. The bishop, who also held the title of Count Palatine from the Norman conquerors, had a castle in Durham, with responsibility of keeping an eye on Scotland not far to the north. William de Wessyngton, having changed his surname to that of the village he had obtained in the trade, was obligated to provide men at arms whenever military aid was required by the bishop. Washington Irving, in his four-volume biography of the first president, says that the condition of military service required of William’s manor was often exacted, and that the service in the grand hunt was far from an idle form:

“Hunting came next to war in those days, as the occupation of the nobility and gentry. The clergy engaged in it equally with the laity. The hunting establishment of the Bishop of Durham was on a princely scale. He had his forests, chases and parks, with their train of foresters, rangers, and park keepers. A grand hunt was a splendid pageant in which all his barons and knights attended him with horse and hound. The stipulations with the Seignior of Wessyngton show how strictly the rights of the chase were defined. All the game taken by him in going to the forest belonged to the bishop; all taken on returning belonged to himself.”

Washington’s great-grandfather, John, arrived in Virginia in 1657, and with his brother, Andrew, bought land in Westmoreland County between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers, land that was good for both farming and hunting. John, according to Irving, “became an extensive planter,” and, as Colonel Washington, he led a force of Virginians and Marylanders against a Seneca tribe that had been ravaging settlements along the Potomac. His estate at Bridges Creek passed in time to his grandson, Augustine Washington, father of the president, and it was in the house on this estate that George was born in 1732. His boyhood was spent in a home in Stafford County, opposite Fredericksburg, and it was here that Washington was soon exposed to the pleasures of the chase.

Survey Work

Washington saw the dogs of poor people when he worked as a surveyor. In a letter from 1749 or 1750, he describes walking all day and sleeping the night with a family before the hearth, “like a Parcel of Dogs or Catts and happy’s he that gets the Birth nearest the fire.” During this work, where inns were often unavailable, he “never had my cloths of [off] but lay and sleep in them like a Negro except the few Nights I have lay’n in Frederick Town.” He would have known of the warmth that a dog can provide on a cold night.

At that time in America, poorer quality shoes were sometimes made of dog leather, and in a letter of November 1759, he directs John Didsbury: “Never more make any of Dog leather.” Thirteen years later, in July 1772, he is required to reinforce this point to the same Didsbury: “I beg that none of the Shoes you now, or hereafter may send me, may be made of Dogskin unless particularly required to be so.”

Lord Fairfax

As a young man, Washington was a favorite of Lord William Fairfax, head of a family with which the Washingtons had been allied for more than a century. Lord Fairfax loved the chase, and found George equally enthusiastic, as described by Irving:

“His lordship was a staunch fox-hunter, and kept horses and hounds in the English style. The hunting season had arrived. The neighborhood abounded with sport; but fox-hunting in Virginia required bold and skilful horsemanship. He found Washington as bold as himself in the saddle, and as eager to follow the hounds. He forthwith took him into peculiar favor; made him his hunting companion; and it was probably under the tuition of this hard-riding old nobleman that the youth imbibed that fondness for the chase for which he was afterwards remarked.”

![]() |

| Map of Mount Vernon drawn by Washington (Wilstach) |

As can be seen from the map Washington made of Mount Vernon, about half of the estate was in woodland, and suitable for hunting.

Even when engaged in other business on his estate, Washington would take dogs with him “for the chance of starting a fox, which he occasionally did, though he was not always successful in killing him.” Such an experienced is described in an entry in Washington’s diary for August 1768: "The hounds havg. started a Fox in self huntg. we followed and run it sevl. hours chase into a hold [sic] when digging it out it escaped."

Hunts were often successful, however, as described in a diary entry for January 1786:

“After breakfast I rid by the places where my Muddy hole & Ferry people were clearing--thence to the Mill and Dogue run Plantations and having the Hounds with me in passing from the latter towards Muddy hole Plantation I found a Fox which after dragging him some distance and running him hard for near an hour was killed by the cross road in front of the House.”

Sometimes, as in modern Britain, foxes were held captive to be released for the chase. A diary entry for October 27, 1787 states: “Went to the Woods back of Muddy hole with the hounds. Unkennelled two foxes & dragged others but caught none. The dogs run wildly & under no command.”

Irving describes hunting as Washington’s passion:

“When the sport was poor near home, he would take his hounds to a distant part of the country, establish himself at an inn, and keep open house and open table to every person of good character and respectable appearance who chose to join him in following the hounds.”

Washington personally treated his dogs for their ailments. A diary entry for September 1768 states: “Anointed all my Hounds (as well old Dogs as Puppies) which appeard to have Mange with Hogs Lard & Brimstone.”

Washington was also concerned with keeping breeding lines pure. An entry for the same month reads: “The Hound Bitch Mopsey going proud, was lind by my Water dog Pilot before it was discovered—after which she was shut up with a hound dog—Old Harry.” An entry for October 1768 indicates the water dog was a spaniel named Pompey.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, an obscure meaning of “line” as a verb is largely restricted to dogs and wolves, meaning copulate, cover. An entry for December 1770 states: “Truelove another Hound Bitch Shut up with Ringwood & by him alone lined.”

An entry for March 2, 1769, is particularly detailed:

![]() |

| First Gentleman of Virginia (John Ward Dunsmore, 1909) |

“Returnd home from my Journey to Frederick &ca. and found that the Hound Bitch Maiden had taken Dog promiscuously. That the Bitch Lady was in Heat & had also been promiscuously lined, & therefore I did not shut her up—That Dutchess was shut up, and had been lind twice by Drunkard, but was out one Night in her heat, & supposd to be lind by other Dog's—that Truelove was also in the House--as was Mopsy likewise (who had been lind to Pilot before she was shut up). The Bitch Musick brought five Puppies one of which being thought not true was drownd immediately. The others being somewhat like the Dog (Rockwood of Mr. Fairfaxs) which got them were saved.”

Sometimes there was sufficient promiscuity that puppies would be drowned automatically, as indicated in a diary entry for June 1768: “Musick was also in heat & servd promiscuously by all the Dogs, intending to drown her Puppy's.”

Drowning puppies that did not fit some concept of the breed involved is not a practice confined to the eighteenth century. Washington continues on March 31, 1769:

“To this time Mopsy had been lind several times by Lawlor as Truelove had been by Drunkard--but as this Bitch got [out] one Night during her Heat it is presumable she was lind by other Dogs especially Pilot, the Master Dog, & one who was seen lying down by her in the Morning.”

There were apparently dogs around the plantation that were either ownerless or perhaps owned by slaves that were not to be permitted to breed with the hunting hounds. A diary entry for December 1770 states:

“Shut up Singer after She had been first lined by one or two Cur Dogs. Jowler being put in with her lind her several times; and his Puppies if to be distinguished saved.”

Naming puppies is described often in Washington’s diaries. An entry for June 1768 says something about how names were chosen: “The hound bitch Mopsey brought 8 Puppys, distinguishd by the following Names--viz.--Tarter--Jupiter--Trueman--& Tipler (being Dogs) --and Truelove, Juno, Dutchess, & Lady being the Bitches--in all eight.”

Dogs could be fixed. An entry for June 1769 states: “James Cleveland [Washington’s overseer for River Farm, one of Washington’s properties] spaed the three hound Bitches Musick, Tipsey, & Maiden as also two hound puppies which came from Musick & Rockwood.”

The rural hunting life came to an end for Washington in 1775 as he became involved in revolutionary activities, though he would renew his passion for the chase after the war was over.

Revolution

![]() |

| Charles Lee (Andrews, 1894) |

Washington was willing to give up the chase, and the company of his hounds, during the course of the American Revolution, but one of his commanders was reluctant to do so.

In February 1777, Major General Charles Lee wrote to Washington:

“I am likewise extremely desirous that my Dogs should be brought as I never stood in greater need of their Company than at present.”

Lee was not related to the distinguished Lees of Virginia but Washington had known him before the war and the two men had no doubt hunted together. Irving says of Lee:

“He was whimsical, eccentric, and at times almost rude; negligent also, and slovenly in person and attire; for though he had occasionally associated with kings and princes, he had also campaigned with Mohawks and Cossacks, and seems to have relished their ‘good breeding.’ What was still more annoying in a well regulated mansion, he was always followed by a legion of dogs, which shared his affections with his horses, and took their seats by him when at table. ‘I must have some object to embrace,' said he misanthropically. 'When I can be convinced that men are as worthy objects as dogs, I shall transfer my benevolence, and become as staunch a philanthropist as the canting Addison affected to be.’”

Washington let his friend down gently as to his wish of bringing his dogs on campaign. A week after receiving the none-too-subtle request, Washington wrote: “Your Dogs are in Virginia. This Circumstance I regret, as you will be deprived of the satisfaction and amusements you hoped to derive from their friendly and companionable dispositions. I am etc.”

Lee, it is to be noted, is responsible for a quip that has considerable currency for a time, describing to Washington in a letter of March 1776 how difficult he found it to position his army, saying he felt “like a Dog in a dancing school. I know not where to turn myself, where to fix myself.”

Victims of War

Horses, dogs, and other domestic animals are often victims of war, and in orders issued in April 1777, Washington commands that an officer and twenty privates be employed to bury “dead horses, dogs, or any kind of Carrion.” In November 1775, Colonel Benedict Arnold’s forces in Canada were starving to a degree that a corporal in a company of Pennsylvania riflemen wrote about having “passed some musketmen devouring two dogs which they had roasted, skin and all, and were making a hearty meal of it, not having eat anything for 2 or 3 days. I saw them offer a Dollar for a bitt of Cake not 2 ounces.”

This was, of course, long before Arnold’s treason. John Adams, an early advocate for Arnold, repeated the words of Arnold’s troops that “he fought like Julius Caesar.” The future president made several analogies regarding Arnold’s detractors and those officers who quarreled among themselves rather than concentrating on the enemy:

“I am wearied to death with the wrangles between military officers, high and low. They quarrel like cats and dogs. They worry one another like mastiffs, scrambling for rank and pay like apes for nuts."

Mastiffs were

Shakespeare’s dogs of war, and were often kept by camp followers to guard military encampments, but whether Adams was imagining their actual use for this purpose during the Revolutionary War is unclear.

An incident occurring in 1779 is worth recounting in connection with the fate of dogs in war. As described by Irving:

“On the 15th of July, about mid-day, Wayne set out with his light-infantry from Sandy Beach, fourteen miles distant from Stony Point. The roads were rugged, across mountains, morasses, and narrow defiles, in the skirts of the Dunderberg, where frequently it was necessary to proceed in single file. About eight in the evening they arrived within a mile and a half of the forts, without being discovered. Not a dog barked to give the alarm—all the dogs in the neighbourhood had been privately destroyed beforehand. Bringing the men to a halt, Wayne and his principal officers went nearer, and carefully reconnoitred the works and their environs, so as to proceed understandingly and without confusion. Having made their observations they returned to the troops. Midnight, it will be recollected, was the time recommended by Washington for the attack. About half-past eleven, the whole moved forward, guided by a negro of the neighbourhood who had frequently carried in fruit to the garrison, and served the Americans as a spy. He led the way, accompanied by two stout men disguised as farmers.”

Destroying dogs that might sound an alarm has, unfortunately but practically, occurred throughout history.

General Howe’s Terrier

An incident during the battle of Germantown, which has become the subject of a book by Caroline Tiger, concerned a terrier that wandered onto the battlefield and was retrieved by Washington’s men. A collar identified the dog as belonging General William Howe, Washington’s opponent. Washington had the dog returned under a flag of truce on October 6, 1777, with an accompanying letter:

“General Washington's compliments to General Howe. He does himself the pleasure to return him a dog, which accidentally fell into his hands, and by the inscription on the Collar, appears to belong to General Howe.”

A footnote to the letter in Washington’s collected papers states that the surviving draft of the letter is in the hand of Alexander Hamilton. Although accounts of this event often emphasize Washington’s humanitarian concern for the dog, his motive was at least in part to establish for Howe that Americans could fight as British gentlemen should, with particular concern for the officers of the opposition and their property.

Peace

With the arrival of peace, Washington attempted to return to the chase. The Marquis de Lafayette promised to provide the general with French hunting hounds, for which Washington thanked him in a letter of July 1785:

“I am much obliged to you my dear Marquis, for your attention to the hounds, and not less sorry that you should have met the smallest difficulty, or experienced the least trouble in obtaining them: I was no way anxious about these, consequently should have felt no regret, or sustained no loss if you had not succeeded in your application.”

![]() |

| Washington and Lafayette, 1794 (Rossiter/Mignon, 1859) |

His seeming patience with the arrival of the dogs was belied by another letter less than a month later to William Grayson:

“Apropos, did you hear him say anything of Hounds which, the Marqs. de la Fayette has written to me, were committed to his care? If he really brought them (and if he did not I am unable to account for the information) it would have been civil in the young Gentleman to have dropped me a line respecting the disposal of them, especially as war is declared against the canine species in New York, and they being strangers, and not having formed any alliances for self-defence, but on the contrary, distressed and friendless may have been exposed not only to war, but to pestilence and famine also. If you can say anything on this subject pray do so.”

The reference to a war against the canine species in New York is unclear to me. There may have been an effort to reduce the number of stray dogs in the city at the time.The French dogs were brought across the ocean by John Quincy Adams, who found the task of escorting them distasteful (apparently the sixth U.S. president was not a dog person). In a letter to Lafayette of September 1, 1785, Washington reveals more about the ultimate source of the animals:

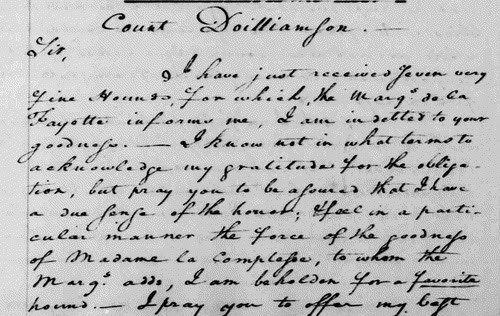

“The Hounds which you were so obliging as to send me arrived safe, and are of promising appearance; to Monsieur le Compte Doilliamson (if I miscall him, your handwriting is to blame, and in honor you are bound to rectify the error); and in an especial manner to his fair Competesse, my thanks are due for this favor: the enclosed letter which I give you the trouble of forwarding contains my acknowledgement of their obliging attention to me on this occasion.”

The partially illegible letter from Lafayette is reproduced in a note by Jackson and Twohig: "French Hounds are not now very easily got because the King Makes use of english dogs, as Being more swift than those of Normandy. I However Have got seven from a Normand Gentleman Called Monsieur le Comte doilliamson. The Handsomest Bitch Among them was a favourite with his lady who Makes a present of Her to You."

This was followed by a letter from Washington to the Comte d’Oilliamson in France:

![]() |

| Washington's letter to Comte d'Oilliamson (Letterbox 12, 187) |

“Sir: I have just received seven very fine Hounds [three dogs, four bitches], for which, the Marqs. de la Fayette informs me, I am indebted to your goodness. I know not in what terms to acknowledge my gratitude for the obligation, but pray you to be assured that I have a due sense of the honor; and feel in a particular manner the force of the goodness of Madame la Comptesse, to whom the Marqs. adds, I am beholden for a favorite hound. I pray you to offer my best respects, and to make my acknowledgment of this favor, acceptable to her: at the sametime I beg you to assure her that her favorite shall not suffer under my care, but become the object of my particular attention. I have the honor, etc.”

A diary entry for September 19, 1785, describes Washington familiarizing his new batch of dogs with his estate: “Took my French Hounds with me for the purpose of Airing them & giving them a knowledge of the grounds round about this place.” One of the French hound bitches had apparently gotten pregnant in transit and had a litter on September 30: “One of the Hound Bitches wch. was sent to me from France brought forth 15 puppies this day; 7 of which (the rest being as many as I thought she could rear) I had drowned.”

Washington enlisted dogs from neighbors to help the French dogs learn the American habits of the chase, as indicated in an entry from November 1785:

“Went out after Breakfast with my hounds from France, & two which were lent me, yesterday, by young Mr. Mason. Found a Fox which was run tolerably well by two of the Frh. Bitches & one of Mason's Dogs. The other French Dogs shewed but little disposition to follow and with the second Dog of Mason's got upon another Fox which was followed slow and indifferently by some & not at all by the rest until the sent became so cold that it cd. not be followed at all.”

Some progress was made with the French hounds by December 1785, according to a diary entry:

“It being a good scenting morning I went out with the Hounds (carrying the two had from Colo. McCarty). Run at different two foxes but caught neither. My French Hounds performed better to day; and have afforded hopes of their performing well, when they come to be a little more used to Hunting, and understand more fully the kind of game they are intended to run.”

Irving believes that Washington was never fully satisfied with the French hounds:

“The passion for hunting had revived with Washington on returning to his old hunting-grounds; but he had no hounds. His kennel had been broken up when he went to the wars, and the dogs given away, and it was not easy to replace them. After a time he received several hounds from France, sent out by Lafayette and other of the French officers, and once more sallied forth to renew his ancient sport. The French hounds, however, proved indifferent; he was out with them repeatedly, putting other hounds with them borrowed from gentlemen of the neighbourhood. They improved after a while, but were never stanch, and caused him frequent disappointments. Probably he was not as stanch himself as formerly; an interval of several years may have blunted his keenness, if we may judge from the following entry in his diary: ‘Out after breakfast with my hounds ; found a fox and ran him sometimes hard, and sometimes at cold hunting, from 11 till near 2—when I came home and left the huntsmen with them, who followed in the same manner two hours or more, and then took the dogs off without killing.’”

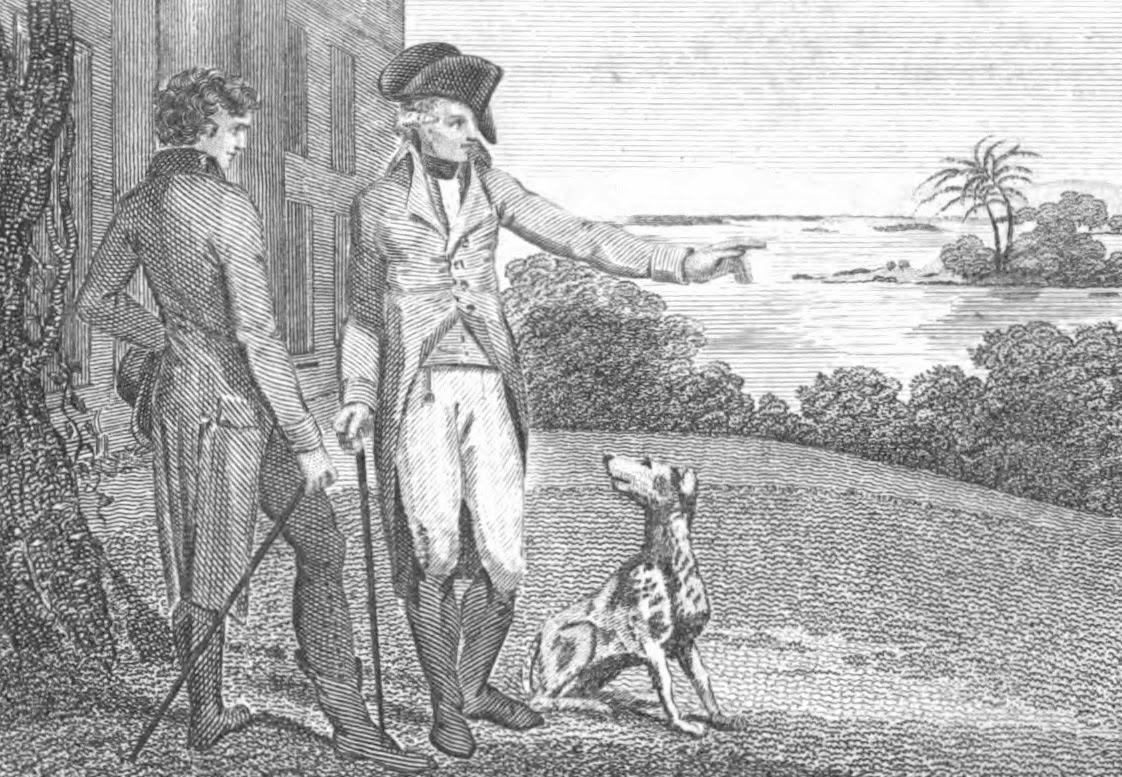

![]() |

| Brissot's interview with Washington, 1788 (published 1797) |

When Jacques Pierre Brissot visited Mount Vernon in 1788, he did not discuss Washinton’s dogs, but a plate in the book of his travels published in 1797 shows Brissot and Washington with one of the hounds.

Curiously, Washington may have gotten rid of his dogs in order to preserve the few deer he had left at Mount Vernon. In a letter to Richard Chichester of August 1792, he writes:

“I have about a dozen deer (some of which are of the common sort) which are no longer confined in the Paddock which was made for them, but range in all my woods, and often pass my exterior fence. It is true I have scarcely a hope of preserving them long, although they come up almost every day, but I am unwilling by any act of my own to facilitate their destruction; for being as much afraid of Hounds (on which acct. I parted with all mine) as the wild deer are, and no man living being able, (as they have no collars on) to distinguish them whilst they are running from the wild deer, I might, and assuredly should have them killed by this means. For this reason as it can be no object since Mr. Fairfax, I am informed, is unwilling to have his Woods at Belvoir hunted, I am desirous of preserving mine. I am, etc.”

Irving recounts that for a time Washington appears to have considered stocking his estate with deer, and that he wrote to England in hopes of getting some deer sent to him. This proved to be unnecessary as a Mr. Ogle of Maryland presented him with “six fawns from his park of English deer at Bellair.”

In late 1793, Washington was informed that a neighbor may have killed one of his deer, though he was perhaps not convinced there was any blame. He wrote to Richard Chichester as follows:

“There must have been some misconception on the part of Colo. Burgess Ball if he understood that I had been informed it was you, who had killed my English Buck; for no such information that I can recollect ever was given to me. I had heard before the rect. of your letter but how, is more like a dream than reality, that that particular Deer was killed on Ravensworth. Nor did I ever suppose that you would have been so unneighbourly as to kill any of my Deer knowing them to be such; but as they had broke out the Paddock in which they had been confined and were going at large, and besides consisted as well of Country as English Deer. I wished to protect them as much as I was able and upon that principle, and that alone, declined giving the permission you asked to hunt some of my Woods adjoining to yours, knowing that they did not confine themselves within my exterior fences, and moreover that, when Hounds are in pursuit, no person could distinguish them from the wild Deer of the Forest.”

A letter of December 1792 refers to the estate’s hound kennel having burned down. I am advised by a current excavator of Mount Vernon that no evidence of a kennel on Mount Vernon has been found in excavations of the site.

Washington may have regretted getting rid of all the hounds, as he realized in time that there could be too many deer on his property. In a letter of January 1797 to James Anderson of Philadelphia, he writes:

“The Gardener complains heavily of the injury which he sustains from my half wild, half tame Deer; and I do not well know what course to take, especially as the hard weather, if it continues, will make them grow more and more bold and mischievous. Two methods have occurred, one or both combined, may, possibly, keep them out of the Gardens and Lawns; namely, to get a couple of hounds, and whenever they are seen in, or near those places, to fire at them with shot of a small kind that would make them smart, but neither kill or maim them. If this will not keep them at a distance, I must kill them in good earnest, as the lesser evil of the two.”

He repeats the idea of getting a few hounds to chase off the deer only a few weeks later in another letter.

Irish Wolf Hounds

In a letter to Lafayette of May 1786, Washington expressed interest in obtaining Irish wolf hounds. Almost two years later, Washington received a letter from Sir Edward Newenham, who described the difficulty in finding such dogs:

“I have just received a letter from your noble and virtuous friend, the Marquis de la Fayette, in which he communicates your wish to obtain a breed of the true Irish wolf dog, and desires me to procure it. I have been these several years endeavoring to get that breed without success; it is nearly annihilated. I have heard of a bitch in the north of Ireland, but not of a couple anywhere. I am also told that the Earl of Altamont has a breed that is nearly genuine; if he has I will procure two from him. The Marquis also wants some at his domain, where he is troubled by the wolves. If mastiffs would be of any service I could send you some large ones, which are our guard dogs; you will honor me with your commands about them. They are very fierce, faithful, and long-lived.”

Writing to Charles Carter, Washington explains his interest in the Irish dog:

“Mastiffs, I conceive, will not answer the purposes for which the wolf dog is wanted. They will guard a pen, which pen may be secured by its situation, by our dogs, and various other ways; but your object, if I have a right conception of it, is to hunt and destroy wolves by pursuit, for which the mastiff is altogether unfit. If the proper kind can be had I have no doubt of their being sent by Sir Edward, who has sought all occasions to be obliging to me. I am etc.”

There is no indication in Washington’s correspondence that he ever got any dogs of this breed. Nor is it clear that he had any actual need to repel wolves. In a letter to Arthur Young in June 1792, he states: “Sheep thrive very well in the middle States, though they are not exempt from deseases, and are often injured by dogs; and more so as you approach the Mountains, by wolves.” Mount Vernon hardly qualifies. Perhaps Washington thought that the wolfhounds could catch the dogs that he imagined slaves were using to rob his flocks.

Dogs of Slaves

Washington expressed his concern about slaves using dogs to steal sheep in a letter to Anthony Whiting of December 1792:

“I am not less concerned to find that I am, forever, sustaining loss in my Stock of Sheep (particularly). I not only approve of your killing those Dogs which have been the occasion of the late loss, and of thinning the Plantations of others, but give it as a positive order, that after saying what dog, or dogs shall remain, if any negro presumes under any pretence whatsoever, to preserve, or bring one into the family, that he shall be severely punished, and the dog hanged. I was obliged to adopt this practice whilst I resided at home, and from the same motives, that is, for the preservation of my Sheep and Hogs; but I observed when I was at home last that a new set of dogs was rearing up, and I intended to have spoke about them, but one thing or another always prevented it. It is not for any good purpose Negros raise, or keep dogs; but to aid them in their night robberies; for it is astonishing to see the command under which their dogs are. I would no more allow the Overseers than I would the Negros, to keep Dogs. One, or at most two on a Plantation is enough. The pretences for keeping more will be various, and urgent, but I will not allow more than the above notwithstanding.”

There is no census of the slaves’ dogs, though at Brissot’s visit in 1788 the slaves numbered 300, “distributed in different log houses, in different parts of the plantation.” Hanging dogs seems to have been a way of shocking slaves into acceptance of the restrictions on their ownership of dogs. This one-dog policy for slaves comes in a letter written while Washington was president. A letter of January 1793 indicates that he may have doubted whether sheep theft could actually be stopped:

“Let Mr. Crow [Hiland Crow, overseer at Ferry and French’s farms] know, that I view with a very evil eye the frequent reports made by him of Sheep dying. When they are destroyed by Dogs it is more to be regretted than avoided perhaps, but frequent natural deaths is a very strong evidence to my mind of the want of care, or something worse, as the sheep are culled every year, and the old ones drawn out.”

It is quite possible that the slaves were active with their dogs at night. This was the only time they had to themselves. John James Audobon, as noted in a

prior blog, described his slaves using their own dogs to hunt wildcat, raccoon, opossum, and such other nocturnal animals as might cross their paths.

It is to be noted that Washington had given orders in the French and Indian War, during a silent march, that all dogs with the army were to be tied up and muzzled or sent back to post. Any dog that remained loose was to be hanged on the spot. Randall, in his biography of Washington, also notes that Washington ordered that any man who discharged a rifle on the march would receive 200 lashes on his bare back on the spot. (It was for his stealthy night marches that Washington came to be known during the American Revolution as the Old Fox.)

Rabies

A diary entry for July 1769 states: “A Dog coming here which I suspected to be Mad, I shot him. Several of the Hounds running upon him may have got bit. Note the consequences.” One of the French dogs Washington got in 1785 was suspected of becoming rabid in 1786. A diary entry for November of that year states:

“A Hound bitch which like most of my other hounds appearing to be going Mad and had been shut up getting out, my Servant Will in attempting to get her in again was snapped at by her at the arm. The Teeth penetrated through his Coat and Shirt and contused the Flesh but he says did not penetrate the skin nor draw any blood. This happened on Monday forenoon. The part affected appeared to swell a little to day.”

In 1797, he sent one of his slaves to Dr. William Stoy in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, in hopes of having him treated before rabies developed from a dog bite:

“Sir: On Monday last, the bearer was Bit by a Small Dog belonging to a Lady in my house, then as was supposed a little diseased. And Yesternight died (I do think) in a State of madness. As soon as the Boy (Christopher) was Bit application was made to a medical Gentleman in Alexandria who has cut out so far as He could, the place Bit, applyed Ointment to keep it open, And put the Boy under a Course of Mercury But being informed of Your success in performing cures on [mutilated] And worse cases, has induced me to send Him to You, and put Him under Your care. Trusting You will do everything in Your Power, to prevent any bad consequences from the Bite, And have at the same time Wrote to Mr. Slough in Lancaster to pay whatever is Your charge, And whenever the Boy arrives do Write me, And Your Opinion of Him, for besides the call of Humanity, I am particularly anxious for His cure. He being my own Body servant. The Mercury will be mostly discontinued upon His leaving this place, and untill He reaches You. And am Sir Yours etc.”

Washington was pleased with the result, as indicated in a letter from March 1798 to Dr. Stoy:

“As I think your charge for the prescription application to Christopher (my servant), who was supposed to be bitten by a mad dog, is a very reasonable one, I send you enclosed a five dollar bank note of Alexandria (having no other paper money by me); without enquiring whether your not having received four dollars before, proceeded from the neglect of the Servant, or any other person. Christopher continues to do well, and I believe is now free from apprehension of any bad consequences from the bite. I shall beg to be informed of your receipt of this letter, being unwilling that you should go unpaid. I am etc.”

“Sir: The President of the U States has reed, your Letter together with a copy of your essay on the disease produced by the bite of a mad-dog. The President has directed me to assure you that his sincere wishes are offered for the useful effects of a work calculated to throw light on a subject so interesting; and to make his acknowledgements for your politeness in presenting it to him. I am etc.”

Mease’s theories concerning the nature of rabies proved superior to those of Benjamin Rush, according to Wasik and Murphy’s recent book on the history of the disease.

Last Dogs

Washington had long been familiar with terriers, which he always spelled “tarriers.” Correspondence for 1796 indicates he had become concerned with breeding them, and wanted to keep this line pure as had been a concern with the hounds:

“I hope Frank has taken particular care of the Tarriers. I directed him to observe when the female was getting into heat, and let her be immediately shut up; and no other than the male Tarrier get to her. I wish you well, and am etc.”

Perhaps, like most people getting old, he began preferring smaller dogs, though in a letter of December 1797 from Mount Vernon, he mentions taking care of a pointer for Thomas Law until Law could send for the dog.

Conclusion

Washington’s English ancestors included avid hunters who understood that

hunting in royal forests and on large estates was an activity not open to all, and to various degrees they benefited by being of sufficient rank to enjoy the privilege of taking game.

They would have understood that commoners, such as peasants living on their lands, and those of the lords they served, were precluded from hunting deer and sometimes other game, both by place and by season, and something of these attitudes likely arrived with them in Virginia in the mid-seventeenth century.

It would go too far to suggest that Washington’s orders regarding the number of dogs his slaves could own was a vestige of the forest law that allowed

killing and maiming dogs that might disturb the peace of the king’s game, but the incident fits within the broader concept that those who owned the land, or had rights to hunt it, could restrict the use of dogs by those of lesser rank who lived on or near such land.

It is not fair to judge our first president by modern concepts of humaneness, nor to expect that he should keep alive dogs for which an estate such as Mount Vernon had no use.

Neither can it be expected that a slave owner would overlook the activities of slaves of which he disapproved, and it is arguable that hanging dogs before their masters was a way of frightening the slaves sufficiently that no punishment would be needed for the owners of the animals.

Nevertheless, it is not appropriate to overlook such facts in an effort to make the first president into a precursor of later cooing pet lovers in the White House.

He lived in an age when dogs were expected to be useful, and likely more than any of his successors in office knew how to make them so.

Note on art: Most depictions of Washington hunting or standing with his hounds date from after his death. As for what Washington himself thought artistic treatment of the chase should show, Jackson and Twohig refer to a print found in Washington's collection at his death, which these authors label, "The Death of the Fox." I am advised by a curator of Mount Vernon that this was part of a series of fox-hunting prints Washington purchased while serving as president in Philadelphia, likely to furnish the executive residence. The

print was made from a painting by John Wootton, now in the Tate Gallery, painted between 1733 and 1736 as part of a series called "Viscount Weymouth's Hunt." This particular painting is specifically entitled:

Thomas, 2nd Viscount Weymouth, with a Black Page and Other Huntsmen at the Kill. The figure in the center holds the limp body of the fox above the heads of the still-eager dogs. (I could find no copy in Wikimedia commons and the Tate would charge me £64 for posting.)

Sources:

Andrews, E. Benjamin (1894) History of the United States (4 vols.) New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Brissot, J.P. (1797). Travels in the United States of America, performed in 1788. In Historical Account of the Most Celebrated Voyages, Travels, and Discoveries from the Time of Columbus to the Present Period (Mavor, Wm., ed.) London: E. Newbery.

Coren, Stanley (2009). George Washington: President, General and Dog Breeder. Psychology Today, January 2, 2009 (describing Washington’s use of the Gloucester Hunting Club in New Jersey).

Ekirch, A. Roger (2005). At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past. New York. W.W. Norton & Co. (describing how slaves were owned by their masters in the day, but sought to conduct their own affairs through the night).

Ellet, Elizabeth (1819). The Women of the American Revolution. New York: Baker & Scribner (mentioning a Newfoundland dog starting a fire in a house by pushing over a lamp, during the advance of the army to Fort Edward).

Fiske, John (1891). The American Revolution, vol. 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin & Co.

Fitzpatrick, John C. (ed.) (1931-1944).

The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, in 39 volumes.

Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (also available online in searchable format at a

University of Virginia website).

Irving, Washington (1856-1859). Life of George Washington (4 vols.). New York: G.P. Putnam.

Nash, Gary B. (2006). The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. New York: Viking Press (mentioning, at xxiv, the only possible instance of a dog in battle during the Revolutionary War that I have so far encountered: “[George] Lippard often dissolve the line between fiction and history in his revolutionary tales…. The story of the muscular Black Sampson of the ‘Oath-Bound Five,’ who avenged the British murder of his white mistress by plunging into the Battle of Brandywine against the redcoats with Debbil, his ferocious dog, was pure fiction.”).

Page, William (ed., 1905). The Victoria History of the County of Durham, vol. 1. London: Archibald Constable & Co. (Quoting the Boldon Book specifically as to William of Hertburn: “William of Hertburn holds WESSINGTON except the church and the land belonging to the church, in exchange for the vill of Hertburn which he quitclaimed for this, and he renders 4 pounds and goes on the great hunt with two hunting-dogs, and when the general aid comes he ought to give in addition 1 mark of the aid.” This source states that the Wessyngtons owed a kind of service called drengage, describing this as follows: “Probably the incidents most characteristic of drengage were the duty of taking part in the bishop's hunt, the 'magna caza,' including the provision of a horse and a dog, which had to be cared for throughout the year, and the obligation of carrying the bishop's messages. “Drengus pascit canem et equum, et vadit in magna caza cum ii leporariis et v cordis . . . et vadit in legationibus' is a characteristic entry that frequently recurs….” This source notes that a dog-kennel (Latin: canillum) was constructed specifically for the great hunt. In addition to providing two dogs, the Wessyngtons were to provide five ropes.)

Randall, Willard Sterne (1997). George Washington: A Life. New York: Henry Holt & Co. (describing, at 101, how the French, in the French and Indian War, had killed shot dogs near Washington's encampment lest the British forces be able to eat them during a siege).

Thacher, James (1812). Observations on Hydrophobia Produced by the Bite of a Mad Dog, or Other Rabid Animal. Plymouth, Mass.: Joseph Avery (quoting extensively from the writings of Dr. James Mease).

Tiger, Caroline (2005). General Howe’s Dog: George Washington, the Battle for Germantown and the Dog Who Crosse Enemy Lines. London: Chamberlain Bros.

Wasik, Bill, and Murphy, Monica (2012). Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus. New York: Viking Books (noting that Mease believed that hydrophobia was a disease of the nervous system, in contradiction to Rush, who categorized it as an inflammatory fever).

Wilstach, Paul (1916). Mount Vernon: Washington's Home and the Nation's Shrine. New York: Doubleday, Page, & Co.

.jpg)